|

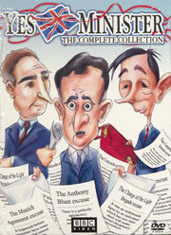

The funniest

scenes are those in which high-ranking civil servants—full of

themselves and convinced that they represent the true government

while politicians are just temporary annoyances—seek to manipulate

the minister. As a comedy, there are obviously exaggerations, but

you can observe the exact same dynamic (sometimes even the same

situations) at the heart of the governments in Ottawa or Quebec City

to this day.

Few people realize to what extent a minister is dependent on his

civil servants for everything. The powers of a minister are far less

impressive than many imagine. He has only a small team—his cabinet

of a dozen or so, only three or four of whom are political advisors,

and most of whom are not specialists in the issues that make up the

minister's responsibilities—to help him make many sometimes very

technical decisions, or set up extremely complex reforms. On the

other hand, thousands of civil servants have been intimately

familiar with their files for years, are masters of the legislative

machine and bureaucratic procedures, and know exactly how to pull

the strings inside an enormous State to obtain or block one thing or

another. They generally control the schedule (it's impossible to push anything forward without jumping through the necessary hoops), the "pen"

(the writing up of texts required to push any file forward), the

expertise (who can you turn to if the civil servants in your legal

department tell you it's against the law to do something, even if

you think they're wrong?), etc.

Few people realize to what extent a minister is dependent on his

civil servants for everything. The powers of a minister are far less

impressive than many imagine. He has only a small team—his cabinet

of a dozen or so, only three or four of whom are political advisors,

and most of whom are not specialists in the issues that make up the

minister's responsibilities—to help him make many sometimes very

technical decisions, or set up extremely complex reforms. On the

other hand, thousands of civil servants have been intimately

familiar with their files for years, are masters of the legislative

machine and bureaucratic procedures, and know exactly how to pull

the strings inside an enormous State to obtain or block one thing or

another. They generally control the schedule (it's impossible to push anything forward without jumping through the necessary hoops), the "pen"

(the writing up of texts required to push any file forward), the

expertise (who can you turn to if the civil servants in your legal

department tell you it's against the law to do something, even if

you think they're wrong?), etc.

A minister who wants to

accomplish anything at all in a direction that does not please the

bureaucracy has to get up pretty early in the morning, pull out all

the stops, and have a strong team with an extremely well-developed

sense of strategy. It's almost like a game of chess. Not that the

minister's own civil servants are the only obstacles to overcome:

there's the Privy Council Office (the Conseil exécutif in Quebec),

the State's central bureaucratic organ; the Prime Minister's Office,

which has the ultimate say on everything; the other ministers; the

caucus; and well-connected lobbyists.

But how is it,

some will wonder, that civil servants can block anything? Are they

not simply subordinates in charge of implementing political

decisions? Yes and no. In fact, they have their own power, and they

use it, even if it's in a roundabout way. There are some classic

tricks that are still constantly being used in our capitals today.

In the TV series, Hacker asks his civil servants, for example, to

formulate a proposition in a certain manner in a document that is to

be presented to cabinet. The document comes back with a formulation

that corresponds rather to Sir Humphrey's position. The minister

sends the document back, asking for modifications. The document

comes back with changes that still do not correspond to the wishes

of the minister, who proceeds to send it back through the machine

again, until at last, discouraged, he decides to try to write it up

himself to his own liking, a task which is obviously more

complicated than he had envisioned.

I would add, from my own

personal experience, that this little game can get even more

complicated when there is a hard and fast schedule to respect (for

example, an important cabinet meeting at which a decision will have

to be made if the whole project is not to be delayed by several

months). Note that civil servants do not engage in direct

insubordination, which they could not do without calling the whole

democratic system into question. They never tell the minister

directly, "We don't care about your position; you're just an

insignificant elected official, and we're the ones with the real

power here." But that is nevertheless how they act, albeit in a more

subtle manner. The minister cannot simply command his civil servants

to do this or that by snapping his fingers. He, too, must play the

game and try to "outsmart" those who are opposed to his reform.

Conversely, if—as also obviously happens—the department's bureaucracy

is rather in favour of the minister's position, then the reform can

proceed much more smoothly.

|