|

Frank Knight's Economic and Social Theology |

|

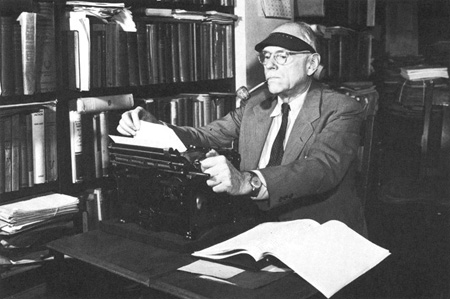

Frank Hyneman Knight (1885-1972), who spent most of his career at the

University of Chicago, where he became a founder of the

Chicago School,

was, from the early 1920s until the late 1950s, one of the world’s most

influential economists.

Milton

Friedman,

George

Stigler

and

James M.

Buchanan

numbered among his students and acolytes. A British economist who taught

at Chicago,

Ronald

Coase,

wasn’t a student of Knight’s; nonetheless, Coase credited Knight as a

major influence upon his thinking.(1)

In 1957 Knight received the American Economic Association’s Francis A.

Walker Award, which was (the AEA subsequently discontinued it) conferred

“not more frequently than once every five years to the living [American]

economist who in the judgment of the awarding body has during his career

made the greatest contribution to economics.”

Knight clarified significant problems of mainstream economic theory and

policy. (As we’ll see, he regarded economic and social matters as at

best imperfectly comprehensible; not infrequently, they were unsolvable

and even unfathomable.) Today he’s best remembered for his book Risk

Uncertainty and Profit (1921).(2)

As time passed, he became more a systematic theologian than an applied

economist.(3)

Economists today typically know or care little about the later Knight;

but it was in this role that the key figures in the Chicago school such

as Friedman and Stigler encountered him and through which he exerted his

greatest and most enduring influence.

If Knight were alive today his views would likely mystify faculty and

students. In the classroom, as Don Patinkin observed,(4)

Knight regularly undertook “long digressions on the nature of man and

society – and God.” His faith was profound. Yet by the standards of his

time and ours, it was quite unconventional. He didn’t consider himself a

Christian: indeed, throughout his academic career he openly (and

occasionally publicly) disparaged “traditional religion.”(5)

He did, however, spend his formative years in a devout family and pious

community; and although as a young man he left in order to pursue his

studies (first at Milligan College, a small Christian institution in

east Tennessee, and later at Cornell University in upstate New York), in

important respects his family’s and childhood community’s ethical and

spiritual precepts never left him. Perhaps that’s why in 1945 he and a

theologian, Thornton W. Merriam, co-wrote a book entitled The

Economic Order and Religion; similarly, in 1950 he dubbed his

presidential address to the AEA as his “sermon” to the profession. And

perhaps that’s why his ashes have been interred in the crypt of the

First Unitarian Church of Chicago.(6) If Knight were alive today his views would likely mystify faculty and

students. In the classroom, as Don Patinkin observed,(4)

Knight regularly undertook “long digressions on the nature of man and

society – and God.” His faith was profound. Yet by the standards of his

time and ours, it was quite unconventional. He didn’t consider himself a

Christian: indeed, throughout his academic career he openly (and

occasionally publicly) disparaged “traditional religion.”(5)

He did, however, spend his formative years in a devout family and pious

community; and although as a young man he left in order to pursue his

studies (first at Milligan College, a small Christian institution in

east Tennessee, and later at Cornell University in upstate New York), in

important respects his family’s and childhood community’s ethical and

spiritual precepts never left him. Perhaps that’s why in 1945 he and a

theologian, Thornton W. Merriam, co-wrote a book entitled The

Economic Order and Religion; similarly, in 1950 he dubbed his

presidential address to the AEA as his “sermon” to the profession. And

perhaps that’s why his ashes have been interred in the crypt of the

First Unitarian Church of Chicago.(6)

How, exactly, was Knight essentially a theologian? He insisted that the

core social and economic problem, and hence the economist’s essential

task, was the “discovery and definition of values – a moral, not to say a

religious, problem.” Indeed, Knight contended that myriad “economic

problems” are mere material symptoms and consequences of a single

spiritual cause – namely man’s innately sinful nature.(7)

More specifically, and according to Nelson,

despite all his outward hostility to Christianity, Knight’s own

[economic] theology … follows surprisingly closely in the Calvinist

understanding of Christian faith. … Human beings in Knight’s view are in

fact corrupt creatures whose actual behavior in the world corresponds

closely to the biblical understanding of the consequences of original

sin.

Richard Boyd demonstrates that Knight’s conception of economics has

“much more in common with [the Christianity of St Augustine of Hippo]

than it does with the [rationalism and utilitarianism of the]

Enlightenment.” Martin Luther, originally an Augustinian monk who came

to despise the rational and mechanical (as he regarded it) theology of

Thomas Aquinas, revived Augustine’s earlier and more pessimistic (with

respect to man’s sinful life in this fallen world) theology. Boyd adds

that Knight’s worldview thus differed fundamentally and perhaps

diametrically from Adam Smith’s, Friedrich Hayek’s and Milton Friedman’s

– all of whom believed, sometimes fervently, in the great “benefits

of progress, development and economic efficiency”.(8)

The Augustinian, Calvinist and Knightian view rejects the mainstream’s

“progressive” vision. The mainstream is utilitarian: the individual

attempts to maximise his own happiness; and politicians, ably advised by

progressive economists, use specific means (economic policy, scientific

management, etc.) to achieve a particular end (the continuous

improvement of material conditions, and eventual universal happiness,

here on earth). “In such matters and in coming down on the Calvinist

rather than the progressive and rationalist side,” Nelson concludes in

Economics as Religion: From Samuelson to Chicago and Beyond,

“Knight was a secular kind of Protestant fundamentalist, reacting

against the thinking of virtually the entire economics profession of his

time.”

From this theological contention sprang fundamental practical

consequences. Not only, for example, did Knight’s theology contradict

Progressive

(hereafter with a lower-case “p”) aspirations for the “value-free”

scientific management of economy and society: it utterly rejected them.(9)

Knight always doubted and often flatly denied that economic and social

engineering could possibly succeed in any meaningful sense. In man’s

fumbling hands, he believed, reason is a frail and unreliable

instrument. Specifically, the baser elements of fallen human nature

always corrupt it; for this reason, it’s usually prone to gross and

sometimes greatly damaging error.

Although Knight’s expression of this view in overtly theological terms

was unusual, it was hardly original. Quite the contrary, it’s anything

but novel. Knight readily acknowledged that this pessimistic view of

human nature and reason is simply the classic (albeit viewed through

non-liturgical Protestant lens) Christian view of fallen human beings

beset by original sin. It’s a long-standing Christian tradition: private

property, the marketplace and largely unfettered (apart from a few basic

prohibitions against aggression, fraud, etc.) trading and investing are

unfortunate but nonetheless necessary concessions to the pervasive

presence of evil in the world. In the past (that is, in the Garden of

Eden) there was no and in the future (namely in heaven) there will be no

private property (or, for that matter, government). Meanwhile, in this

world, stable and secure rights to property and the active pursuit of

profit are means to maintain a semblance of peace and order. Orthodox

Christianity has long contended, in Richard Schlatter’s words, that

“since the Fall the natures of men, all of them depraved, make necessary

… the division [into private ownership] of property …”(10)

Viewing matters through a non-liturgical Protestant lens, Knight

emphatically denied that an anointed priesthood of “expert” economists

could possibly escape the shackles of the general human condition.

Progressive economists, in other words, were depraved sinners just like

everybody else; as a result, they were equally prone – nay, given their

tendency towards hubris, even more likely than the humble generalist and

layperson – to fall into and remain in error. In this dissenting (to the

progressive orthodoxy) theology, economics, politics and the

welfare-warfare state are not our salvation, and economists and

politicians are not our saviors. Quite the contrary: they’re false

prophets.

According to Nelson,

Knight marks the beginning of a fundamental break of the Chicago school

with the Progressives of [Paul]

Samuelson’s

ilk, a new assumption that self-interest will be expressed not only in

the marketplace but also in the actions of government and indeed perhaps

in every area of society. It’s profoundly insightful, but it’s hardly

novel: it’s simply a secularised form of an old view, characteristic of

[John]

Calvin

and other

Protestant

Reformers,

that sin has fundamentally and irredeemably … invaded every aspect

of human existence. While Roman Catholic theologians also recognised the

centrality of sin in the world, they tended to evince considerably

greater faith in human reason and in the possibilities for rational

striving toward improvement in the human condition.(11)

Not a Typical Chicagoan

Knight was a founder and leader of the Chicago School. But his means and

ends never conformed completely – or sometimes even comfortably – to

those of Friedman, Stigler and other prominent Chicagoans. He stoutly

defended market liberties; yet he also partly blamed alleged advocates

of the market – including some of his own colleagues at Chicago – for

the wholesale turn to European socialism and American progressive

principles, and resultant severe erosion of morality and liberty, that

occurred during his lifetime. In the 19th century a “religion

of liberalism had a positive social-moral content.” The 20th

century, alas, was a different story. “One of the main factors in the

present crisis,” he sagely wrote during the Great Depression, “is that

the public has lost faith, such faith as it ever had, in the moral

validity of market values.” Elsewhere he added: “the real breakdown

of bourgeois society is only superficially economic; … fundamentally,

however, [it] is … moral.” In short, classical liberalism had made a

basic “intellectual mistake” because it had “failed to see that the

social problem is not at bottom intellectual, but moral.”(12)

And in his view, no adequate moral defense of the free market could or

did emerge from his colleagues at Chicago.

|

|

“Knight was a founder and

leader of the Chicago School. But his means and ends never

conformed completely – or sometimes even comfortably – to

those of Friedman, Stigler and other prominent Chicagoans.” |

|

Knight lamented that the typical economist’s description of the market

as a “competitive” system had been “calamitous for understanding” of the

ultimate merits of a market system. Buying and selling in the market,

Knight saw, is ultimately desirable not because the resultant

competition reduces costs and prices to the lowest feasible levels. If

it were, then the case for the free market could be put in conventional

(that is, progressive and utilitarian) terms of efficiency. But it

isn’t: instead, buying and selling in the market provides the one

practical mechanism for resolving in a satisfactory way – namely one

that preserves individual freedom – the tensions among values and

preferences that accompany the development of any large and diverse

society. Knight contended that the market’s advantages should be

understood as the promotion of a “pattern of cooperation” among people

who come together on a non-coercive basis for mutual advantage. Even

people whose belief systems differ fundamentally are able, by buying and

selling in the market, to co-operate without sacrificing their diverse

values to some common set of norms. You needn’t like or otherwise

associate with Person X (be he an atheist, agnostic, lukewarm Christian,

devout Jew, etc.); but if he offers you a good or service you desire at

a price you’re happy to pay, then both benefit.

Accordingly, action in the market minimises coercive interactions.

Indeed, in a market “there are no power relations.” It enables each

person “to be the judge of his own values and of the use of his own

means to achieve them.” A Christian can trade as easily with a Muslim as

with a fellow Christian; if, however, each must first confess the same

faith, then no exchange will likely occur. Here too, Knight’s views

reflect their Christian and specifically Calvinist origins. In Christian

theology, it’s important to emphasise, private property and markets are

products of original sin. In an ideal world, neither would exist. But

ours is hardly an ideal world. In this world, property and markets

provide outlets to blunt human strivings for power and advantage. Knight

didn’t say so explicitly, but his views suggest that he rightly regarded

private property, markets and capitalism as gifts from a loving God to

his reprobate children.

Knight’s Progressive Bêtes-Noires

The theology of some of Knight’s critics – whose Christian faith,

incidentally, also underpinned their conception of economics and views

about appropriate economic policy – also help to clarify his thoughts.

Perhaps most notably, the principal founder of the American Economic

Association,

Richard

Ely,

argued early in his career (subsequently he curbed his rhetoric’s

enthusiasm, but he never tempered its thrust) that the biblical

commandment “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself” rather than

self-interest should underpin social behavior. Accordingly, one could

not “serve [both] God and mammon; for the ruling motive of the one

service – egotism, selfishness – is the opposite of the ruling motive of

the other – altruism, devotion to others, consecration of heart, soul

and intellect to the service of others.” For Ely, particularly in the

Social

Gospel

phase of his life during the 1880s and 1890s, observed Nelson,

the chief motivating force in the world – even in labor and business –

must be “love” of fellow human beings, rather than the “self-interest”

long favored by most economists. Ely’s attitudes in this respect were in

fact representative of those of many leading progressive intellectuals,

often associated with the Social Gospel movement.(13)

This, Knight contended, was dangerously muddled thinking. Specifically,

in Calvinist terms it was utterly and indeed dangerously mistaken.

Specifically, it was a major instance of a general phenomenon – namely

how progressive intellectuals had substituted a fuzzy and “romantic”

conception of human nature for a clear and realistic approach. It’s

simply impossible, Knight contended, to apply “the ‘love’ doctrine” as

a guiding principle “over, say, the population of a modern nation – and,

of course, it must ultimately be over the world since, for a world

religion [like Christianity], national boundaries have no moral

significance.” Similarly, Knight rejected the economic determinism and

the resulting hope for a radical improvement in the condition of the

world (perhaps, if and when the economic problem could ever be finally

solved, attaining a state of affairs where “love” would in fact rule)

that characterised progressive theory and policy. “There is no reason,”

he contended,

to believe that if all properly economic problems were solved once [and]

for all through a fairy gift to every individual of the power to work

physical miracles, the social struggle and strife would either be

reduced in amount or intensity, or essentially changed in form, to say

nothing of improvement – in the absence of some moral revolution which

could by no means be assumed to follow in consequence of the change

itself.(14)

As Knight saw it, the core assumptions of the American progressive

gospel – namely that economic events are the driving forces in history,

and that economic progress is not just possible but, if guided by

progressive economists, inevitable – constituted an egregious misreading

of the human condition. The mere achievement of mass material

abundance cannot – either easily and quickly, or with great difficulty

over a long time – abolish the pervasive presence of sin in the world.

Indeed, material plenty can worsen spiritual poverty:

The idea that the social problem is essentially or primarily economic,

in the sense that social action may be concentrated on the economic

aspect and other aspects left to take care of themselves, is a fallacy,

and to outgrow this fallacy is one of the conditions of progress toward

a real solution of the social problem as a whole, including the economic

aspect itself. Examination will show that while many conflicts which seem

to have a non-economic character are “really” economic, it is just

as true that what is called “economic” conflict is “really” rooted in

other interests and other forms of rivalry, and that these would remain

unabated after any conceivable change in the sphere of economics alone.(15)

The Oppressive “New Religion” of Misguided Reason

Knight, remember, didn’t regard himself as a Christian. Instead, he saw

himself as a critic of Christianity and believed that in the past the

Church had often violated its creeds – and had thereby threatened man’s

liberty to act according to his conscience. In the modern age, however,

the Church was no longer the greatest threat to freedom. What was? The

new “milieu in which science as such is a religion.” This new religion –

of which economics was regrettably a significant and growing part –

promoted a “gospel” that involved “salvation by science.” This

“salvation,” moreover, reflected the old natural-law precept that

promised salvation through strict adherence to God’s laws. These

progressive follies (as Knight regarded them) were simply the latest

manifestation of a long tradition (centuries ago, priests succumbed to

it; early in the 20th century, academics followed suit) of

pandering to power and oppression in the name of reason.(16)

Bluntly, progressives had perverted science and concocted a Golden Calf.

Knight saw great danger in the increasing tendency during the 20th

century of economists to mimic and worship physical scientists. The

danger commenced in the mistaken belief that human behavior was subject

to laws and principles analogous to the laws of physical sciences. The

conviction that economists would discover more of these laws, and

thereby better explain this behaviour, increasingly accurately extended

the danger; and the ambition that they could predict and even manipulate

(“reform”) it in order to achieve the ends of their political masters

(“economic policy,” “social policy,” etc.) highlighted its invidious

consequences. This tendency, as Knight watched it harden into orthodoxy,

expressed social scientists’ unspoken – and craven – motives: “Any

attempt at use of the unqualified procedures of natural science in

solving problems of human relations,” he disclaimed, “is just another

name for a struggle for power, ultimately a completely lawless one.”

Just as the construction of a dam in order to control a river depends

upon knowledge of physical science, the advocates of the “scientific

management” of society seek to use social science as means to control

people.(17)

Given the frailty and unreliability of reason and the depravity of man’s

fallen nature, from Knight’s point of view the results of “scientific

management,” “social engineering” and the like are not merely bound to

fall well short of progressives’ expectations: their consequences,

unintended or otherwise, will be negative. Specifically, given the

self-interest of rulers and the priesthood of economists upon whose

advice they rely – the evisceration and eventual extinction of human

freedom will follow in scientific management’s wake. Progressive

economists’ grand schemes reflect their faith that the world is a

rational place. But this faith is mistaken; accordingly, “human nature

being as irrational as it is,” these schemes inevitably fail. In order

to solve social problems, according to the progressive mindset, all that

is needed “is that intellectual leaders … be converted to the scientific

point of view.” Apparently it’s really that simple: “the social problem

will be solved by the application of scientific method.”

Such thinking, Knight retorted, is mere “scientistic propaganda.” The

“fetish of scientific method” in the study of society “is one of the two

most pernicious forms of romantic folly that are current among the

educated.” Indeed, a fully rational “science of human behavior, in

the literal sense, is impossible” and a “natural or positive science of

human conduct” is “an absurdity.”(18)

A key reason is that ideas of social scientists can alter the behaviour

of the people they study. Moreover, even if a true science of society

were possible it wouldn’t be desirable.(19)

An individual whose behavior is perfectly and scientifically predictable

is not a real human being: he’s an automaton. Self-consciousness and the

ability to choose – the existence of “free will” in the Christian

formulation – distinguish people from beasts. If humans’ economic

behaviour really were as deterministic as (say) biologists conceive the

behaviour of animals, then what in moral and spiritual terms

distinguishes a man from a dog?(20)

It may well be, as Knight noted, that “the idiot” is the happiest human

being; but the mere pursuit of pleasurable sensation “is not what makes

human life worth-while”.(21)

Knight’s protest is powerful. As he readily acknowledged, however, it’s

hardly original. Four centuries earlier, and in a similar vein, Martin

Luther protested that the Roman Catholic Church had imperiled human

freedom by encouraging the faithful to believe that the good life in

this world and the attainment of salvation in the hereafter were simple

matters of rigorous and unreflective adherence to the hierarchy’s

mechanical rules. Even if there’s considerable truth to the idea that a

human being is a biological entity governed by laws of physical nature

(which surely there is), the rational methods of science can hold “no

clue to the answer to the essential problems of free society,” and the

living of lives of genuine “spiritual freedom”.(22)

The Lutheran Reformers, in opposition to the Roman Catholic orthodoxy of

their time, emphasised the scriptural truth that salvation is sola

fide (“by faith alone”) – and that faith is a gift that’s a mystery

to man and comprehensible only to God. In these regards, Knight’s

economic and broader social theology – not only its creed that original

sin undermines any human effort to act rationally, and indeed underpins

some of man’s most evil actions – broadly reflects protestant theology.

Martin Luther often invoked St Paul’s message that “the flesh lusteth

against the spirit and the spirit contrary to the flesh” and therefore

“so that ye cannot do the things that ye would do.”(23)

Like the Protestant Reformers, Knight doubted the benefits of human

“works.” He rejected the optimistic faith that the scientific management

of society (the secular counterpart of “works”) is the path to the

eventual perfection – or even great improvement – of human existence.

Contrary to the rationalist theology of Thomas Aquinas and the

mechanical prescriptions of contemporary economics, no mere set of rules

can ever show the way to heaven – here on earth or otherwise. For this

reason, Ross Emmett concluded that Knight’s thinking constitutes an

essentially theological view of the basic economic choices facing any

society:

In a society which has no recourse to the providential nature of a God

who is present in human history, the provision of a justification for the way society works is a “theological” undertaking. Despite the fact that

modern economists often forget it, their investigations of the universal

problem of scarcity and its consequences for human behavior and social

organization is a form of theological inquiry: in a world where there is

no God, scarcity replaces moral evil as the central problem of theodicy,

and the process of assigning value becomes the central problem

of morality. Knight’s (implicit) recognition of the theological nature

of economic inquiry in this regard is one of the reasons for his

rejection of positivism in economics and his insistence on the

fundamentally normative and apologetic character of economics.

In some sense, therefore, it is appropriate to say that Knight

understood that his role in a society which did not or could

not recognize the presence of God was similar to the role of a

theologian in a society which explicitly acknowledged God’s presence. As

a student of society, he was obliged to contribute to society’s

discussion of the appropriate mechanisms for the coordination of

individuals’ actions, and to remind the members of society that their

discussion could never be divorced from consideration of the type of

society they wanted to create and the kind of people they wanted to

become.(24)

|

|

1. See Ross B. Emmett's overview of Knight's thinking in

The Elgar Companion to The Chicago School of Economics, Elgar, 2010, p. 238.

2. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit describes and explains Knight's

conception of the entrepreneur's role in economy and society. It's best-known

for its distinction between economic risk and uncertainty. The outcomes

of "risky" situations (such as the toss of a fair coin) are unknown but

nonetheless governed by "known" (that is, plausibly assumed)

mathematical-statistical models called probability distributions. Knight

contended that these situations, where concrete rules (such as the

maximisation of expected utility) can be applied and accurate and

reliable probabilities can be computed, differ fundamentally from "uncertain"

situations (such as the survival and growth of a new enterprise). In

these latter situations, not only the outcomes but also the probability

distributions that generate them are unknown. Uncertainty, Knight argued,

presents to entrepreneurs the opportunity to generate economic profits

that perfect competition (in the sense that economists normally

understand the term) cannot eliminate.

3. Razeen Sally, "The Political Economy of Frank Knight: Classical

Liberalism from Chicago," Constitutional Political Economy, vol. 8, no.

2, 1997, pp 123-138 and Ross B. Emmett, "Frank Knight: Economics versus

Religion," in H. Geoffrey Brennan and A. M. C. Waterman, eds., Economics

and Religion: Are They Distinct? Kluwer, 1994, pp. 118-119.

4. Essays

on and in the Chicago Tradition, Duke University Press, 1980, p. 46.

5. See in particular William S. Kern, "Frank Knight on Preachers and

Economic Policy: A Nineteenth Century Anti-Religionist, He Thought

Religion Should Support the Status Quo," American Journal of Economics

and Sociology, vol. 47, no. 1 (January 1988), pp. 61-69.

6. The First Unitarian Church of Chicago is a Unitarian Universalist ("UU")

church. Unitarians share no common creed and include people who confess

a wide variety of personal beliefs - including deists, pantheists,

polytheists, pagans, agnostics and others. See James Ishmael Ford, Zen

Master Who? Wisdom Publications, 2006, p. 187. See also James M.

Buchanan, "The Economizing Element in Knight's Ethical Critique of

Capitalist Order," Ethics, vol. 98 (October 1987) pp. 246, 247.

7. See in particular Knight's article "Ethics and Economic Reform:

Christianity" in Economica, vol. 6, November 1939, pp. 398-422.

8. "Frank Knight's Pluralism," Critical Review, vol. 11, Fall 1997, pp.

537-554.

9. See in particular Knight, "Pragmatism and Social Action,"

International Journal of Ethics, vol. 46, no. 2 (January 1936), pp.

229-236.

10. Private Property: The History of an Idea, Russell and Russell,

Rutgers University Press, 1951, p. 35.

11. Economics as Religion: from Samuelson to Chicago and Beyond, p.

120.

12. Knight, "Social Science and the Political Trend,"

University of

Toronto Quarterly, vol. 3, 1934, pp. 280-287 and Knight, "Ethics and

Economic Reform: The Ethics of Liberalism," Economica, vol. 6, no. 21 (February

1939), pp. 1-29.

13. See also Frank H. Knight and Charles Howard Hopkins,

The Rise of

the Social Gospel in American Protestantism, 1865-1915, Yale University

Press, 1940.

14. "Ethics and Economic Reform," p. 408.

15. "Ethics and Economic Reform," p. 410.

16. Knight, "Pragmatism and Social Action," p. 53; Knight,

"Salvation by Science: The Gospel According to Professor Lundberg," Journal

of Political Economy, vol. 55 (December 1947), pp. 537-52; and Daniel J.

Hammond, "Frank Knight's Anti-positivism," History of Political Economy,

vol. 23, no. 3 (Fall, 1991), pp. 359-381.

17. Knight, "The Limitations of Scientific Method in Economics," in

The

Trend of Economics, ed. Rexford Tugwell, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, pp.

229-67; Knight, "Free Society: Its Basic Nature and Problem,"

Philosophical Review, vol. 57, no. 1 (January 1948), pp. 39-58; and

Richard A. Gonce, "Frank H. Knight on Social Control and the Scope and

Method of Economics," Southern Economic Journal, vol. 38, no. 4 (April

1972), pp. 547-558.

18. Knight, "Abstract Economics as Absolute Ethics,"

Ethics, vol. 76,

no. 3 (April 1966), pp. 163-177 and Knight, "Salvation by Science: The

Gospel According to Professor Lundberg," Journal of Political Economy,

vol. 55, no. 6 (December 1947), pp. 229-230, 235.

19. Knight, "The Role of Principles in Economics and Politics," pp.

261, 258, 260, and Knight, "Economic Psychology and the Value Problem,"

Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 39, no. 2 (May 1925), pp. 372-409.

20. Among contemporary economists, one ?nds the clearest echo of

Knight's thinking in the writings of his former student James Buchanan.

Indeed, on many subjects Buchanan sounds remarkably similar to Knight.

For example, Buchanan considers that a person who behaves strictly

according to scienti? c laws "could not be concerned with choice at

all." Indeed, it is "internally contradictory" to speak of individual "choice

making under [scienti? c] certainty." If human dignity and freedom

require the power to choose, and if the ability to do either good or

evil must be within the scope of individual decision making, then,

Buchanan believes, scientific rules cannot determine human behaviour.

Indeed, "the scienti? c view of a human being as mechanical instrument

denies a person his or her basic humanity." See James M. Buchanan,

What

Should Economists Do? (Liberty Press, 1979), p. 281.

21. See Knight, "The Role of Principles in Economics and Politics,"

American Economic Review, vol. 41, March 1951, p. 279.

22. Knight, "The Free Society: Its Basic Nature and Problem,"

Philosophical Review, vol. 57, no. 1, 1948, pp. 39-41.

23. John Kohl, "Christianity: Protestantism," in R. C. Zaehner,

Encyclopedia of the World's Religions, Barnes and Noble, 1997, p. 101.

24. Ross B. Emmett, "Frank Knight: Economics versus Religion," in H.

Geoffrey Brennan and A. M. C. Waterman, eds., Economics and Religion:

Are They Distinct? Kluwer, 1994, pp. 118-19. |

|

|

From the same author |

|

▪

Austerity, What Austerity? Europe Desperately Needs

"Genuine Austerity"

(no

317 – December 15, 2013)

▪

The shameful treatment of Ron Paul by the mainstream

media

(no

300 – May 15, 2012)

▪

The Evil Princes of Martin

Place – Introduction

(no

286 – February 15, 2011)

▪

The return of Keynesianism

(no

278 – May 15, 2010)

▪

Why do we have recurrent economic booms and busts?

(no

262 – December 15, 2008)

▪

More...

|

|

|

First written appearance of the

word 'liberty,' circa 2300 B.C. |

|

Le Québécois Libre

Promoting individual liberty, free markets and voluntary

cooperation since 1998.

|

|